There are vast sums of money lying around in unclaimed estates, and lots of unsuspecting heirs: eligible individuals and next of kin, who are oblivious to the fact that they are owed money. Left unclaimed, the banks and insurance companies are often the beneficiaries of these ‘assets in purgatory’.

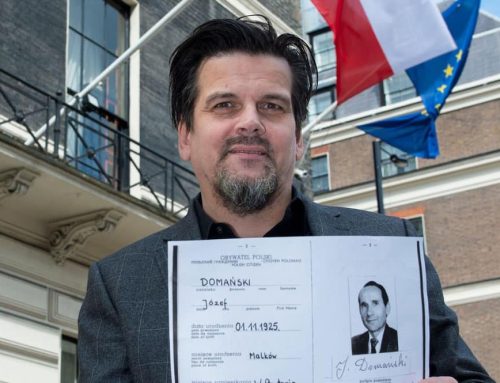

It may seem a morbid field in which to run a business, with death being the stock in trade, but it didn’t stop heir-hunting entrepreneur Danny Curran from launching Finders International, which specialises in reuniting next of kin to assets they often didn’t realise were theirs.

The subject of BBC reality TV programme Heir Hunters, the former one-man detective operation is now expanding into the US, Australia and South Africa, and already has a successful operation in the Republic of Ireland.

Curran credits much of his recent success to technology and the transparency afforded by new digital footprints. But when he first started out in the pre-Google 1990s, he tracked down heirs the hard way. He says: “I’d left school at 16, moved to London and most of the time worked two jobs, handing out magazines in the mornings and working behind bars at night. Then I met someone in the heir tracking business, and at the age of 26 decided to launch one of my own.”

This was long before the days of online search engines, so Curran spent hours at London record offices, such as Somerset House and St Catherine’s House, scouring vital records and indexes on paper or on microfiche.

“My turning point came when I worked out how to beat the competition, that had become complacent,” he said. “At that time notices of unclaimed estates were advertised weekly in the national press. I discovered that the newspapers first appeared at a major railway station in London, so I drove up there at midnight, collected the papers, and went to the office to start work.”

Curran began his pursuit of inheritance trails, unearthing harrowing stories of forgotten family members, break down of relationships, reconciliation, and situations left unresolved by two world wars, and meeting individuals whose lives were changed forever by windfalls they didn’t know about.

Most of the work is referred to Finders by lawyers, local councils, hospitals and coroners, but Curran still competes against other firms when the Government advertise unclaimed estates. “The work is triggered by a person dying, whose estate is known about, but whose heirs may be missing or unknown,” he explains. “If people come to us with a definite tale to tell about how they need our help, we may assist, but unfortunately there are too many stories of people who think their grandfather missed out on millions, which turn out to be flawed anecdotes, and are statute barred in any event.”

While there are occasions where large estate values worth millions are discovered, in the majority of cases individual entitlements are not likely to be large. “This is because the estates often need to be divided by next of kin,” says Curran. “In one case £10,000 was shared between 17 eligible beneficiaries. Average estate values are currently between £20,000 ($25,000) and £50,000 ($64,000).”

Therein lies the element of risk for his business; the share they end up with – in general, heir hunters charge a fee of between 10% and 25% of an inheritance – doesn’t always compensate them for the time they’ve spent investigating. The other downside is the long lead-time to payment, typically 12 to 18 months after work has been completed.

Technology, too, has transformed the heir hunting industry, and not always for the better. “We now have to deal with the Internet offering multiple research leads, some of which are flawed and irrelevant, and others which have had their information transcribed wrongly,” says Curran.

Growth has been enhanced by the formation of the International Association of Professional Probate Researchers, Genealogist & Heir Hunters, a regulatory body for an unregulated industry, set up by Curran last year. “International collaboration with overseas professionals has widened the scope of the service we provide which has led to growth,” he says.

And his vision for the future is of increased social isolation as populations continue to grow. “More people are living alone which will only lead to more assets remaining unclaimed, especially across borders. We want to work with the rest of the world, raising standards and awareness for the greater good. We’re in the good news business after all.”

Source: This story first featured in Forbes Magazine