Down thin cobbled lanes around Old Street is a warehouse, and inside – assuming you are a British citizen born before the year 2000 – sits a microfiche with your name on it.

The warehouse in question belongs to Finders International, a firm that (as readers who watch daytime TV may recall) provides the genealogists on the BBC’s Heir Hunters. Among a myriad of other things, the business tracks down the rightful heirs to unclaimed estates, and vice versa.

I’m with Danny Curran, Finder’s founder and chief executive. For a man who spends his days trawling through birth, death, and marriage records, he’s awfully chipper.

Curran joined the industry in 1990, when a friend offered him a job. But he never intended to set up his own firm.

“It happened by chance,” he says. “And then, it was in adversity really. I fell out with them and I think maybe I wanted to go a bit further with the company than they did. I had to start from scratch – borrowed money on my credit cards and kept my fingers crossed.”

Finders seekers

Today the firm, in its second iteration, has offices in London, Edinburgh and Dublin. Curran’s television stardom naturally played a role in the firm’s success in commanding a £50m industry.

At the start though, he says across the same desk he used back then, it wasn’t so easy.

“I was working in the office during the day, and there was nothing on the internet in terms of searching, so we had to go to a place called the Family Record Centre (FRC). They opened two evenings a week and on Saturdays. So I worked during the day at the office, then went up to the FRC during evenings and Saturdays. Then I wrote the reports on Sunday and started again on a Monday.”

Explaining what the firm actually does, chuckles Curran, can be quite boring. They pick up estates where the next of kin is unknown from all over the place – whether public reference, a solicitor, or a local council.

Generally, it is someone who has died without relatives, leaving an empty property. What Finders does is sort of in the name – it finds the next of kin. I ask if he ever gets any nutters calling him up.

“Oh of course! Plenty of nutters. There’s the pie in the sky story, where you get someone who calls and says ‘my great grandfather owned half of New York and I’m the sole heir to everything’ – I’ve stopped doing those to be honest. There’s a statute of limitations anyway, so even if you could prove it, it wouldn’t go through the court.”

“People often come to us. There might be a couple of names on a will and they can’t place them, or they don’t know who they are, or it’s a badly written will.

“More commonly, they’re trying to find all or some of the family that’s missing. So they’ve established the estate dissolves on aunts and uncles who are deceased, and their descendants. They’ve found two or three, but they have no idea where the rest of them are. So they need us to track those people.”

A new record

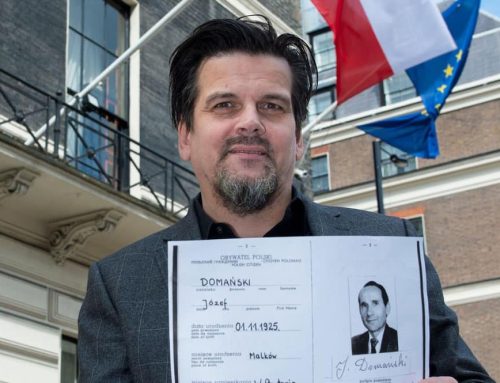

The industry, sitting in a grey area as it does, is riddled with regulatory issues. The digitisation and privacy of records in the UK, for example, are worthy of several tomes that one cannot envy the future author of. Curran was involved in one of the first attempts at putting records online, but even today, it’s not as simple as one might assume.

“We bought every birth, marriage, and death record in England and Wales from 1837 to 2000ish. And then after an interim period of CDs and DVDs it went online, and we had to subscribe to get the data. Then, in 2006, they decided that no one is going to see any death indexes anymore. Privacy loomed its head again, so ironically, here we are in 2017, going to Westminster Library every day to check death records on microfiche – it’s absurd.”

Along with other international firms, last year Curran set up an industry association, the International Association of Professional Probate Researchers, to regulate the practice.

“There’s voluntary regulatory bodies. There’s associations that have been set up by other firms that are really just self serving – let’s get our friends to join a club – this is an international one to regulate a vastly unregulated industry.

Issues with flip-flopping government bodies are commonplace. The government division Bona Vacantia, which by law passes ownerless property to the Crown, is advertised online. Curran says that because they are listed without any attached value, very often his team end up spending time researching worthless assets.

“That’s the work we do,” he says. “We have to accept a certain amount of write-offs. But one of the most frustrating things is, they used to do a very basic, very cheap search for will.”

A record number of claims are being listed as intestate, that is, without the deceased having made a will. But Curran says that in a fifth of cases where a property is listed so on the Bona Vacantia website a will does exist.

“If somebody has made a will, there’s no formal registry. The central probate people can lodge the will of the deceased, and it will get searched for. But often the will gets left with a solicitor. So the idea is that they write to all the local solicitors, they say ‘no, no will here’ and the government advertise it as unclaimed with no will.

“But that process is not infallible. They’re claiming money for the Crown ostensibly.”

Curran warns that the number of unclaimed estates listed by Bona Vacantia is attracting fraudsters keen to pocket inheritances. “This is an unregulated industry and councils do little research before paying out an inheritance,” he says.